Luxury vs. Obligation: Israelite Burials in 19th-Century Paris

Kaylee P. Alexander, PhD | July 3, 2020

In 1804, following decades of cemetery complications in major cities such as Paris, Napoleon issued a series of burial reforms that were to radically transform the ways in which French citizens would henceforth be buried. Still the basis for French burial laws to this day, the Decree of 23 Prairial year XII (June 12, 1804) guaranteed, for the first time in French history, distinct burial plots in public cemeteries for all citizens regardless of class or religion. However, burial would only be permanent for a small fraction of the population who met the considerable financial criteria for purchasing a perpetual concession, a land grant that transformed a plot public cemetery territory into private property where one could establish a family vault in perpetuity.(1) According to my ongoing dissertation research using the daily inhumation records at the Archives de Paris, these plots constituted less than 6% of burials in the nineteenth century, while all others took place in temporary concessions (renewable in five-year increments), or, even more often, in free plots within public territory (limited to just five years).

Map of Père-Lachaise Cemetery with the enclos israélite (div. 7) highlighted by author in yellow. Source: Roger et fils, Le Champ du Repos (Paris: Lebégue, 1816).

23 Prairial also brought with it the beginning of the end for cult-specific burial grounds in Paris, meaning that burial rites were now subject first and foremost to the regulations of the state. Prior to 1804, this had not been an issue, as burial remained largely the domain of religious bodies throughout France. Just as the churchyards had served local Catholic communities throughout France, the Jewish community, too, had established private cemeteries controlled by the local rabbinate.(2) Beginning in 1809, when the Jewish enclosure was established in the seventh division of Père-Lachaise Cemetery, all Jewish burials in Paris were required to take place within the municipal cemeteries. This meant that Jewish burials, regardless of any religious obligation, could no longer escape public burial laws, including the state-regulated concession system (see, for example, Isabelle Meidinger and Gérard Nahon). This would prove to be particularly problematic for the Jewish community, as the exhumation and dispersal of remains was strictly prohibited by halakha(religious law).

While the financial barriers of the concession system relegated the vast majority of Parisians to free five-year plots within the modified fosses communes (common graves), the Jewish community would, by 1870, establish the Société le Repos éternel,a charity organization dedicated to the procurement of perpetual burials for their less fortunate co-religionaries. Appalled by the system of burial concessions that privileged the memory of rich above all others, the le Repos éternel aspired to completely eliminate the need for what one news article called the “hideous fosse commune” (Benoît-Lévy, 48).

In 1870, directed by Benoît Lévy, the Repos Éternel began issuing compartments within burial vaults of perpetual concessions at highly subsidized rates, supported primarily by individual donors. According to a handful of surviving annual reports, individuals became honorary members of the society by pledging at least five francs. Among the Repos éternel’s most notable donors was the chief rabbi of France, Zadoc Kahn (1839–1905), as well as members of the Rothschild family—who together contributed roughly one thousand francs annually—and the prominent banker and art collector, Moïse de Camondo (1860–1935).

Using the contributions of its honorary members, the Repos éternel purchased perpetual concessions and constructed family-style crypts with eighteen burial compartments each, priced at 1,800 francs (equal to about a year’s salary among the working class). Those who could not afford to purchase perpetual plots on their own could then request one of these compartments within the shared society vaults. Compartments were made available and priced according to financial need, with a “full-priced” compartment being sold at one hundred francs. Subscribers would pay an initial five francs for the burial of their loved one, which included not only the burial compartment, but also a zinc plaque bearing the name, age and birthplace of the deceased. The remaining fee was made payable in monthly installments of one franc; upon completion of payment the subscriber would receive a definitive title declaring ownership of the compartment. Those who could not afford the full price were eligible, at the discretion of the community rabbis and the society’s honorary members, to receive compartments discounted as low as twenty francs or, in exceptional cases, for free.

Annual Report of Société Le Repos Éternel (1873). Collection of the Archives de Paris (1326W 50). Photograph by author.

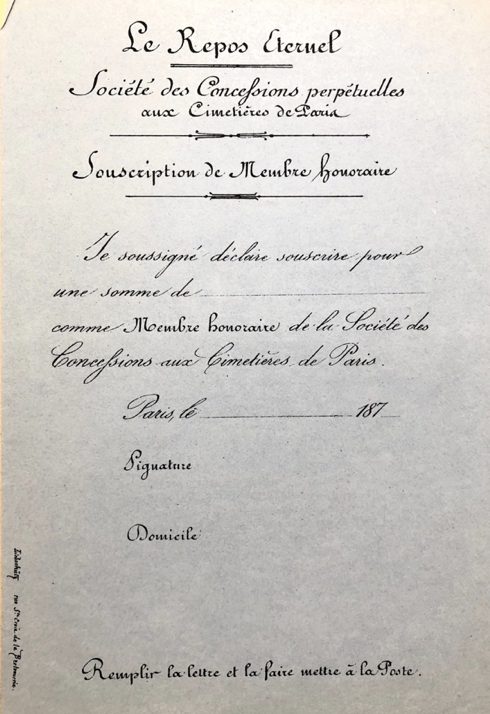

Sample membership form for the Société Le Repos Éternel. Collection of the Archives de Paris (1326W 50). Photograph by author.

The society flourished over the course of the 1870s and 1880s such that by 1888 over 2,600 people who had otherwise been destined for the fosse commune had benefited from the society’s affordable and free burial compartments (“Nouvelles diverses,” 1888: 247). Although article 14 of the law of 23 Prairial had specified that concessions only be granted to relatives and successors of the deceased, the Repos éternel successfully, in 1879, argued against an 1878 letter from the Minister of the Interior that sought to reinforce this statute against the society. Petitioning the Municipal Council of Paris, the society argued that the existing concession system was unjust because it deprived the poor of the same rights to commemoration as the rich and they thus sought to uphold their position as a proxy relative to those who could not afford perpetual concessions on their own. Ultimately the commission sided with this argument, finding “that there is no reason to deprive the indigent of an advantage hitherto reserved for the rich, and that by authorizing associations such as [the Repos éternel], we pay homage to the principle of equality that should prevail in our institutions.”(3) Thus, the Repos éternel was permitted to continue operating as proxy relatives for the indigent deceased.

By the end of the century, under the leadership of the society’s third president, Simon Alexandre (1830–1903), they had secured enough funds annually to be able to further reduce the price of their compartments for all prospective beneficiaries (“Nouvelles diverses,” 1903: 154). It is unclear as to precisely when the Repos éternel officiallydisbanded, although he society had met challenges similar to those of 1878 on at least two other occasions, as the question of whether or not burial vaults constructed for use by those not directly related to one another conformed to the strictest interpretations of 23 Prairial was contestable. Around 1907, the legitimacy their collective vaults must have come into question as an Ordre de service issued by the Préfecture du Département de la Seine on March 19, 1907 determined (as Conseil Municipal de Paris had in 1879) that the society would be permitted to continue not only using the vaults they already owned, but also to acquire new ones.(4) Seemingly debates over the legality of these collective vaults arose simultaneous to mounting concerns over how to manage the increasingly limited burial space within the city. By 1878, for example, it had already become necessary to establish additional cemeteries outside of Paris to accommodate the growing demand for concessions. It appears that any excuse to restrict the number of new perpetual burials was welcome, and the beneficiaries of the Repos éternel appeared to have been a relatively easy minority target. Sometime between 1907 and 1922, collective vaults such as those operated by charities such as the Repos éternel were banned outright, although there is some indication that operations may have continued somewhat clandestinely until around 1923, when perpetual concessions, too, met their end.

By 1930 the Society was no longer accepting support and were, at least provisionally, nonoperational. This was likely due not only to the restrictions that had been placed on them in accordance with the Decree of 23 Prairial, but also because of the simple fact that perpetual concessions were no longer available in any Parisian cemeteries. In 1923, the municipal government decided to permanently replace the perpetual concession with fifty-year plots that were indefinitely renewable at the discretion of the surviving family members of the deceased. Following the announcement of this news, one contributor to L’Univers Israélite wrote:

The concession in perpetuity does not fulfil for us “a respectable feeling rooted in a longstanding custom,” but rather to a tradition that has the force of religious law and that prohibits the exhumation and disposal of a dead person’s remains. That which is a luxury elsewhere, is in the Israelite cult an obligation. As well, our less fortunate coreligionists suffer from the prohibitive tariffs that the city has set for perpetual concessions, especially since the administration, strictly interpreting the law, has prohibited [the use of] collective vaults constructed by charitable brotherhoods. With the new project, even the rich themselves will no longer be able to conform to the rites of their religion.

[…] We have seen Israelites save franc by franc the amount necessary for the purchase of a concession, in fear that no one, at their death, would want to or be able to carry out this duty; how could perpetuation be left to hypothetical heirs? (“Concessions à perpétuité,” 1922: 344–345)

Although the potential for permanent burial remained, it could never again be guaranteed.

Notes

Although since the twentieth century the temporal status of perpetual concessions has been called into question, in the nineteenth century these burial contracts were understood to be permanent agreements between individuals and the state.

This still remains the case in some areas outside of the Paris metropolitan area, notably in Alsace-Lorraine. See: Isabelle Meidinger, “Laïcisation and the Jewish Cemeteries in France: The Survival of Traditional Jewish Funeral Practices,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 1, no. 1 (2002): 37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725880110120424.

Conseil Municipal de Paris, “Rapport présenté par M. Morin, au nom de la 2e Commission (1), sur une demande formée par l’Œuvre du Repos éternel, à l’effet d’être autorisé à acquérir des terrains dans les cimetières de Paris” (1879).

Préfecture du Département de la Seine, Ordre de service nº 112 (March 19, 1907), Archives de Paris (1326W 30).

References

“Concessions à perpétuité.” L’Univers Israélite, December 29, 1922. RetroNews.

“Nouvelles diverses.” L’Univers Israélite, January 1, 1888. RetroNews.

“Nouvelles diverses.” L’Univers Israélite, April 24, 1903. RetroNews.

Benoît-Lévy, Edmond. “Le Repos Éternel.” L’Univers Israélite, October 1, 1888. RetroNews.

Conseil Municipal de Paris. “Rapport présenté par M. Morin, au nom de la 2e Commission (1),

sur une demande formée par l’Œuvre du Repos éternel, à l’effet d’être autorisé à acquérir des terrains dans les cimetières de Paris.” Paris, 1879. Accessed February 12, 2020, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6317371g.

Karo, Joseph. Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh De’ah [1563 CE], 363:1–3. In Code of Hebrew Law, translated by Chaim N. Denburg. Montreal: Jurisprudence Press, 1955. Accessed January 14, 2020, https://www.sefaria.org/.

Meidinger, Isabelle. “Laïcisation and the Jewish Cemeteries in France: The Survival of Traditional Jewish Funeral Practices.” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 1, no. 1 (2002): 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725880110120424.

Nahon, Gérard. “Jewish Cemeteries in France.” In Jüdische Friedhöfe und Bestattungskultur in Europa, edited by Esther Bertele and John Ziesemer (Berlin: Bäßler, 2011): 77–81, https://doi.org/10.11588/ih.2011.0.20216.

Préfecture du Département de la Seine. Ordre de service nº 112 (March 19, 1907). Archives de Paris (1326W 30).

About the Author

Dr. Kaylee P. Alexander is a writer, editor, and visual culture historian specializing in cemeteries, funerary monuments, and the cultural economics of burial in France and the United States. Approaching issues of survival bias, ephemerality, and erasure in the cemetery, she employs data-driven and digital methodologies to study vernacular memorial practices, particularly in instances where little material evidence has survived into the present day. Her first monograph, A Data-Driven Analysis of Cemeteries and Social Reform in Paris, 1804–1924, was published with Routledge's Research in Art History series in 2023. She is co-editor-in-chief of the Radical Death Studies blog and treasurer for the Collective for Radical Death Studies.