Justice for Nadia: Remembrance and Grief from Femicides in Mexico

Marlene Melissa Davila | July 10, 2021

Death is never easy. Not even in a country where millions celebrate Día de los Muertos surrounded by cheerful music and colorful decorations, as a means of remembering their deceased loved ones. For most, death is a journey of grief and sorrow that ends with resilience: “moving on” as we tend to call it. But for those like Blanca Martínez, who lost her daughter, Nadia, in March 2020, it is a never-ending journey of unresolved pain and loss.

On March 8, 2020 (International Women’s Day), Nadia was violently murdered while driving to her home in Salamanca. To date, no suspects have been arrested, and her case remains unsolved.

This is a harsh reality for an average of ten women per day in Mexico, who fall victim to violent deaths at the hands of partners, family members or unknown men as in Nadia’s case. These murders are understood as first and second-degree murders, in which the killing is intentional. In Mexico, these deaths can be categorized more specifically as femicides: the intentionally violent murders of women.

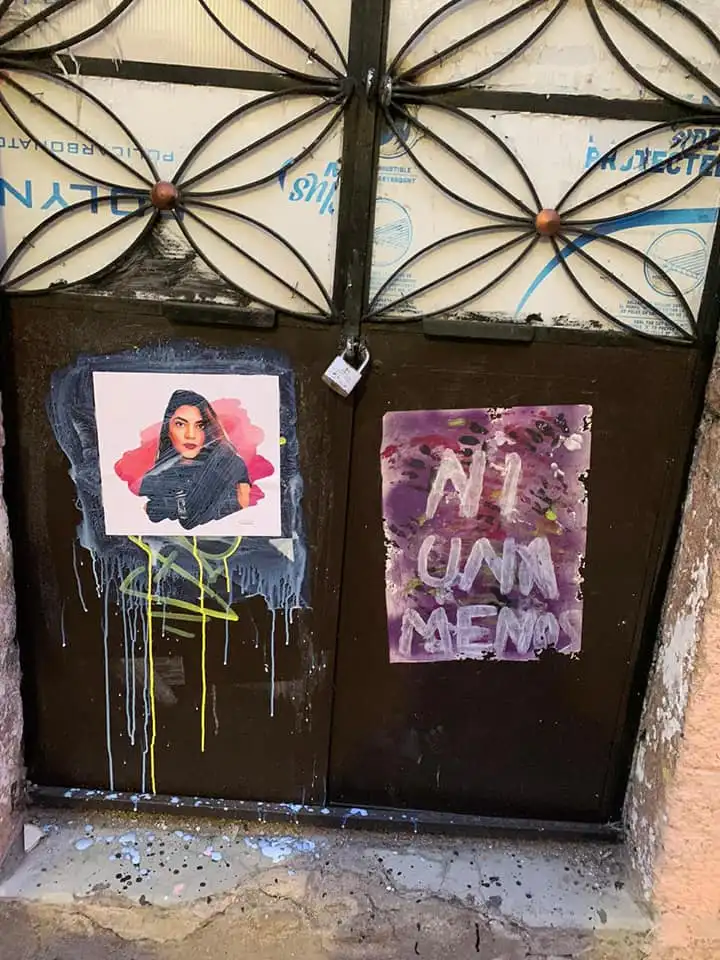

Unknown author, 2020.

Mexico’s Penal Code (article 325) states that femicide is committed when someone deprives a woman of her life for reasons specifically related to their gender, and the sentence for this type of crime is up to 65 years imprisonment. Even though this has been stated by the law, the reality of this sentence is far-fetched, as only an average of 3 out of every 100 murders of women have been ruled femicides. Animal Politico’s research also showed that 80% of female murders were not even categorized as serious crimes.

In the context of impunity and corruption that leave cases like Nadia’s unsolved; and the only way to deal with the tragic death of a loved one is to demand justice through protest.

Nadia Verónica Rodríguez Saro Martínez was a young and bright student enrolled in the International Relations program at the Universidad Iberoamericana in León, Guanajuato. She was always looking for ways to help others and wanted to work with the United Nations to support women facing gender violence. Her friends have described her as fun, and full of energy and dreams.

But her dreams would never be fulfilled. Murdered violently as she was driving home on March 8, 2020, just a few days after having posted the following about femicide and disappearances on her Facebook page: “If one day it’s me please take care of my niece because I wanted to be an example for her and overall teach her how to live without fear and fight for life. Because if one day it’s me, I want to be the last one.”

Two days after her death, a catholic funeral service took place for her and the Universidad Iberoamericana organized a temporary altar decorated with pictures, messages and flowers where Nadia’s family, friends and peers could speak and grieve together. The head of the university promised that they would do everything in their ability as an institution to seek justice for Nadia.

March 10,2020 was an emotional day that prompted a number of actions intended to remember Nadia and demand justice for her and her family. Several local and national newspapers, as well as the university network, covered Nadia’s murder and made knowledge of her case widespread. However, after some weeks had passed, Nadia’s case appeared to be, regrettably just another forgotten femicide.

From April to September 2020, her parents, Blanca Martínez and Bernardo Rodríguez continued to visit the state’s commissioner of Salamanca to get updates on their daughter’s murder. However, their petitons were ignored, and the commissioner gave no answers. Nadia’s friends also faced obstacles with the university who had once promised to do whatever they could to get justice for Nadia.

Unfortunately, the process of coming to terms with violent deaths for many Mexicans means seeking justice on their own, as local authorities tend to ignore petitions, and, in some cases, are colluding with the same criminals who are responsible for these violent crimes.

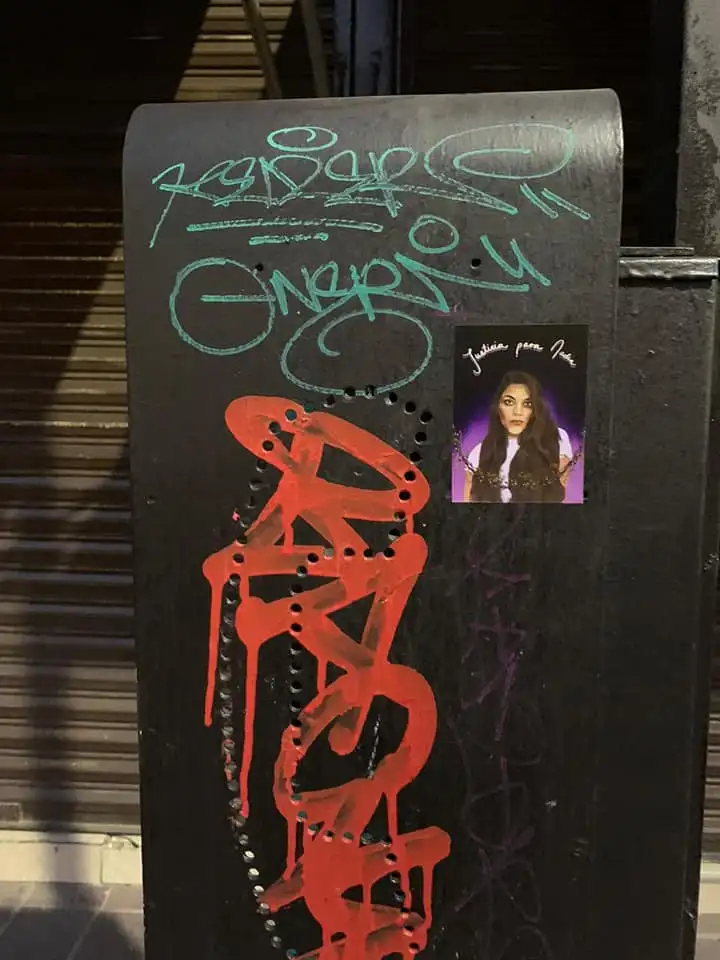

Colectiva Sorelle, 2020.

In a moment of despair, Nadia’s friends and other students from the Universidad Iberoamericana founded the “Colectiva Sorelle,” a feminist group that seeks justice for Nadia. The group took action with a massive movement to post stickers and create public artworks in two cities: Nadia’s hometown (Salamanca) and the city of León, where Nadia had once been a student. This first effort sought to remind both cities of Nadia and the countless other victims of femicide with phrases like “Ni una menos” (not one more). Most of these works were portraits of Nadia created by Colectiva artists and close friends.

On October 8, 2020 the group took action again in Salamanca’s letters, covering them with phrases like “Justice for Nadia” and “Salamanca is a femicide city.” It did not take long, however, for the police and local authorities clean up the letters and throw away these messages and pictures.

On October 9th, the Colectiva made an even bigger statement. This time with media coverage; Nadia could not be forgotten. The Colectiva, joined by Nadia’s mother, protested outside of the university with banners and photographs. They chanted and sang songs like “Canción sin Miedo” by Vivir Quintana throughout the evening.

They also invited several newspapers to cover their protest and presented the university with a petition demanding support their call for answers from the police, as well as a safety protocols and psychological services for female students. Their actions were replicated in several Mexican Ibero and ITESO university campuses, creating a widespread message: “Nos falta Nadia” (Nadia is no longer with us). The police questioned the women involved several times throughout the protest and tried to intimidate them, but the Colectiva persisted.

Nadia’s mother, Blanca, and the Colectiva gather outside of the university campus.

In the following months the university began publicly responding to the Colectiva’s petitions and meeting with students to follow up on Nadia’s case to pressure the state’s commissioner. There are still no concrete answers, but these dialogues continue to address a number of related issues from student sexual harassment, to campus safety measures, and how to remember Nadia.

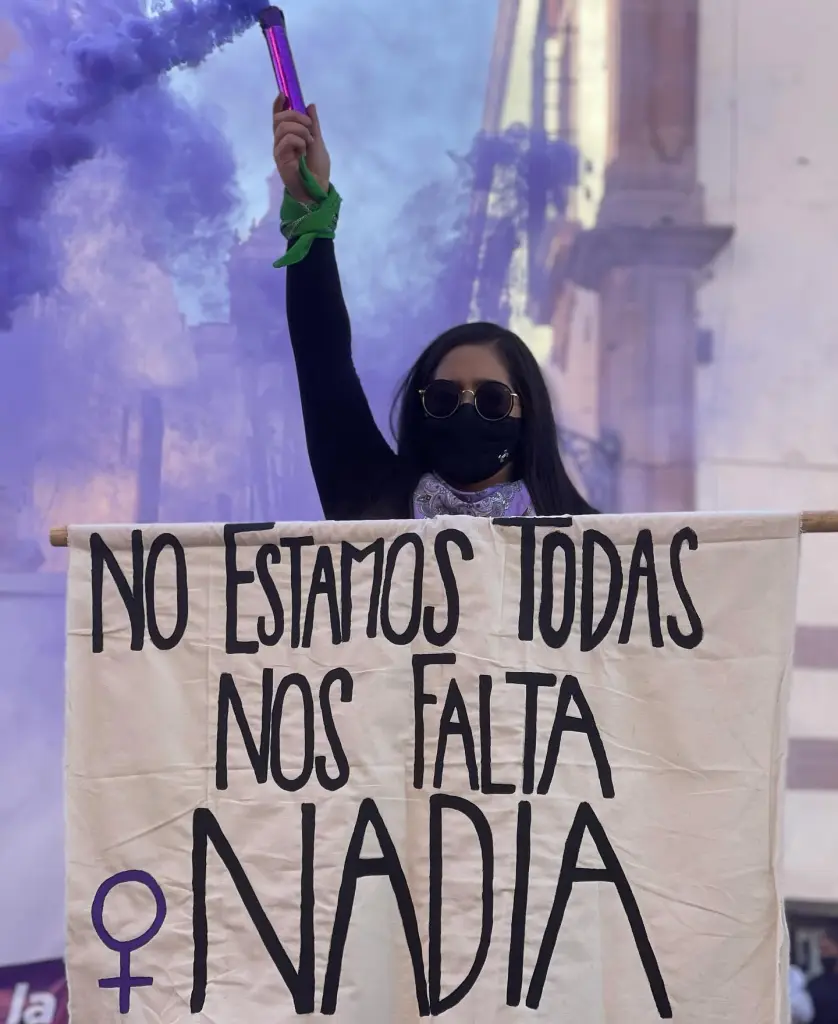

Another feminist protest took place for Nadia and other victims of femicide in the city of Zacatecas, Mexico. The purple smoke is used to represent the feminist movement Aranza Martínez, 2021.

In November 2020, the Colectiva created an altar for Nadia during Día de los Muertos to remember her, as many traditionally do for this Mexican holiday). Music was played, friends left photographs, messages, and foods that Nadia enjoyed. We still remember Nadia today in various ways from a local documentary “Nadia, Presente” (2021) to a colorful mural painted on the university’s campus and a book that compiles memories of her from family and friends. Nadia’s Mural was painted by local artists in the university campus, with the phrase she last wrote on her Facebook profile: “If it’s me one day, I want to be the last one.”

In recent years and in combination with actions on a local level, feminist groups have been organizing protests and making visual statements to demand the local and federal governments to take action in the femicides that happen each day. The groups’ courage to speak up has mobilized the country’s protest culture, where thousands of women now join forces to tackle gender violence.

Barriers placed in order to “protect” the Government Palace in Mexico City from feminist groups were covered with flowers, crosses and names of femicide and homocide female victims. Nadia’s name was written among hundreds of others.

Even with rememberance, the grief and pain are never forgotten, Nadia’s mother wrote for the Collective for Radical Death Studies the following testimony:

“I had a family based on love; an excellent husband and two beautiful children: Nadia and Juan. But on March the 8th 2020, International Women’s Day, we received a call that changed our lives. They had killed my daughter Nadia, who at the time was 22 years old, in Salamanca’s Boulevard. We didn’t know if it would be categorized as a femicide or homicide. But what I can say is that in that moment, I felt my life was over. I couldn’t believe that my daughter; an excellent student, daughter, sister and friend was gone.

It’s sad to think that she became another number of gender violence in Mexico. After more than one year nothing has changed, we still don’t have answers.

As a mother I felt devastated, without the will to carry on living. My life didn’t have meaning with the pain I was going through. But still, I thank God for the miracles that happened in these difficult times: the support from her friends, as well as several institutions and her university…even people I didn’t know. But specially, my husband and son who gave me the support I needed to carry on.

I know that my daughter was taken away from me in the most cruel way. However, I also know that she will always be there for me: guiding and taking care of me. Nadia will live through me and through those who wish to remember her.

I wish her death will not be in vain and can become a movement to raise consciousness and stop violence against women.

Thank you to everyone who has cared and has been supportive towards our family.

My name is Blanca and they killed my daughter in the worst possible way.”(1)

For many young students Nadia became a symbol of resistance. Her picture is still seen on social media and around the university campus and throughout the city. Nadia will not be forgotten, and neither will the thousands of femicide victims whose cases remain unsolved.

From an outside perspective, Mexico and its traditions such as Día de los Muertos may seem joyous and colorful, however, all the color seems to fade away when those we honor and remember were victims of violent, unresolved crimes.

Notes

1. The author reached out to Nadia’s mother informing her of the work being done at the Collective for Radical Death Studies and how this blog entry could help spread awareness on femicide and Nadia’s case. Blanca wrote this heart felt letter for CRDS and our blog readers.

References

Angel, A. (2020). Suben penas por feminicidios, pero solo 3 de cada 100 asesinatos de mujeres son esclarecidos y llegan a condena.

Audelo, S. (2021). En Saltillo Cambian Nombres de Calles en Memoria de Vícitmas de Feminicidio.

Azteca Noticias (2020). News on Nadia’s murder.

Castillo, N. (2021). El Día que Salamanca le Quitó la Voz a Nadia.

El Comercio. (2020). Nadia Rodríguez, la estudiante que fue asesinada en pleno Día de la Mujer en México.

Espinosa, V. (2020). Fiscalía de Guanajuato y la Ibero olvidaron el crimen de Nadia, denuncian sus padres.

Poplab, (2020). Ibero León colaborará para esclarecer el asesinato de Nadia.

Rangel, A. (2021). Con protesta en Morelia, piden esclarecer feminicidio de Jessica González.

About the Author

Marlene Davila was born in the Mexican state of Guanajuato in 1998. She grew up in England and lived, for some time, in Belgium. Marlene began her research and interest in death studies and cultural perspectives on death when she fell ill with a rare type of cancer. Her diagnosis changed her perspective on life and death and so she began her research and interest in death studies and cultural perspectives on death.