Burial, Memory, and the East St. Louis Pogrom of 1917

Jeffrey Smith, PhD | February 19, 2024

It happened in every city in America. When the new interstate highways came through, people were displaced, buildings razed, neighborhoods destroyed or divided as state departments of transportation and city planners sought to superimpose a highway system on existing cities. East St. Louis, Illinois, had one notable difference from others. An exit ramp covered two cemeteries—Lawn Ridge closest to the street, was for white folks; Douglas, behind it, was for African Americans. Supposedly, it included people killed in perhaps the worst racial pogrom in US history. When the highway came through in 1968, the State relocated some 3,000 Black bodies—or so it said. In 2019, however, road crews found bones from older graves, and some, like Malissa Blanchard who grew up in the area, think some of those bodies are still under the highway.

Our search for the dead goes back to the riotous violence on July 2 and 3, 1917. It blared from the front pages of almost every newspaper in the United States. While historians and journalists have written about the deaths in the aggregate—numbers, causes, the shocking sheer brutality of them—the fate of the bodies of those dead is absent. We know about the deaths of some, but not about the scores of undocumented deaths. We know almost nothing at all about the burial, mourning, and commemoration of any of those dead. So, how do these deaths inform the broader narratives of cemeteries and mourning intersecting with Jim Crow?

East St. Louis was an industrial suburb across the Mississippi River from St. Louis from its beginning. Population grew rapidly every decade; the Black population of the city was some six thousand souls by 1910, or about one in nine city residents. By 1917, estimates are that this had doubled, so that some 18 percent of the city’s population was African American. The number burgeoned in early 1917, as southern, rural Black folks came to the city for wartime jobs. Tensions rose that spring when white workers at the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) went on strike and management brought in replacement workers—you know, scabs—from the South. ALCOA turned to the same source for replacements as the meatpacking industry did the year before: southern, rural African Americans. Racial violence started in late May against African Americans, including as many as three thousand white men marching downtown, compelling Illinois Governor Frank Orren Lowden to send in the National Guard to suppress further violence.

This headline from the St. Louis Argus, the leading Black newspaper at the time, not only detailed the events in July 1917, but made clear that white people were the aggressors against blameless Black folks. Image: Newspapers.com.

The pogrom started when two white men drove through a Black neighborhood and fired some shots. When another car came through an hour or so later, area African Americans fired, assuming they were the same people; this time, the unmarked car held two white police officers, both of whom were killed. Police left the bloodstained car on display in town for thousands to see. Armed mobs gathered and assaulted Black neighborhoods. They beat and killed Black men, women, and children indiscriminately for two days, burning entire blocks of neighborhoods and the people inside. Some African Americans escaped across the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge in droves; others tried to flee attackers by jumping into culverts and drainage canals that carried them into the Mississippi River and beyond, never to be seen again. Some were incinerated in an opera house when they refused to come out and be killed by rioters. St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter Carlos Hurd rightly reported that in East St. Louis, “black skin was a death warrant.” Estimates of the death toll by everyone from the local police chief to observers like Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. DuBois ranged from a hundred to more than two hundred. After the first day of violence, the Post-Dispatch reported that “the bodies of 21 negroes, beaten, shot, clubbed and stoned to death, one of them a 2-year-old girl, were in two undertaking establishments.” They were no doubt at one of the two African American–owned funeral homes in town, those of RMC Green and the Nash Brothers.

The outrage among African Americans was captured in this political cartoon juxtaposing the violence against Black folks in East St. Louis against President Woodrow Wilson’s public assertions that “the world must be made safe for democracy.” Image: Wikipedia.

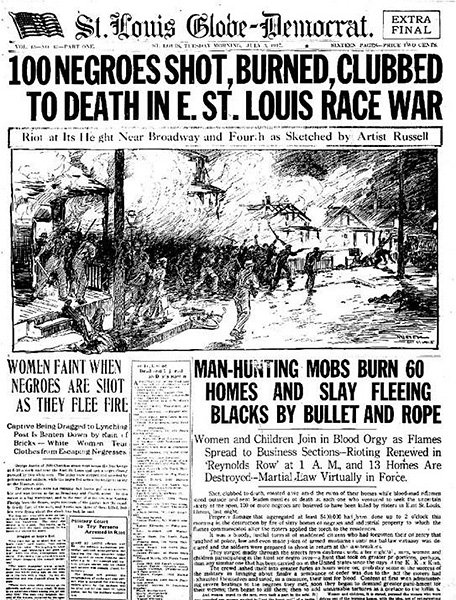

Troops lined the streets of East St. Louis as violence erupted over two days in July 1917. Part of the military’s job was to try to protect African Americans from further violence from white mobs. Meantime, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat called the pogrom a “race war,” referring to white “mobs” roaming the streets. Image: Newspapers.com.

About the same time that Douglas Cemetery opened in 1903, Russell McCullen Green opened business as the first African American undertaker in East St. Louis, followed by the Nash Brothers a decade or so later. By 1915 Green had abandoned horse-drawn hearses in favor of motorized ones and had opened branch funeral homes in Black neighborhoods throughout St. Louise by the early 1920s. Anecdotal evidence credits both Charles Nash and Green with using their hearses to move people to St. Louis during the pogrom, “saving countless lives.”

The funeral business was a foundation for both economic and social stature in the Black community at the turn of the century. Booker T. Washington recognized the importance of the profession in 1907 when he observed that “with the exception of that of caterer there is no business in which Negroes seem to be more numerously engaged or one in which they have been more uniformly successful” in that undertaking, and Green was no exception.

Yet there is no record of where any of the known dead from the pogrom are buried except the Post-Dispatch’s report of the two morticians. None. Family members probably had the remains of some shipped back home. Locally, the best candidates are the two African American cemeteries at the time: Douglas Cemetery and a public cemetery known as St. Clair Cemetery, which included a potter’s field that accepted African Americans. Lawn Ridge and Douglas fell into disuse after World War II, and records appear to have met unfortunate fates. Then the State of Illinois expanded the interstate system through St. Clair County; the cemeteries were located right where the I-64/SR111 interchange was planned. The State hired Keeley Construction Company to exhume and reinter the bodies. After receiving complaints about moving bodies in pickup trucks, Keeley was compelled to purchase eleven used hearses for the grisly task. Several people remember seeing them leave every day. Dennis Reynolds, for example, (then a student at neighboring Assumption Catholic High School) remembers “some of my teachers saying that those were the graves for people who couldn’t afford a funeral home or proper burial.” Historical topographical maps bear out the teacher’s hypothesis, with the area that would have been Douglas Cemetery labeled as “Potter’s Field” as early as 1934. Since the cemetery was apparently municipally operated, burials there probably did span the economic spectrum, but it’s unlikely that it was exclusively used for the impoverished. The company and the State may have even thought they had removed all the bodies, or at least the ones they could find. They were wrong. Unmarked graves were missed, exhumations didn’t happen as planned. These things just happen.

The early map of Lawn Ridge and Douglas cemeteries only identifies the white Lawn Ridge. The second circle to the east sits in the center of a future cloverleaf. The aerial photos from 1955 show the location of the cemeteries right in the middle of the cloverleaf entrance ramp onto I-64 west. The line and circle of trees just to the right of the center is what remained of Douglas Cemetery. Image: Historic Aerials.

Reportedly, the exhumed bodies went to two African American cemeteries, Sunset Garden of Rest and Booker T. Washington, but that’s doubtful. The interment records for Washington for the summer of 1968 are bereft any mention of removals from Douglas or anywhere else. In fact, the records don’t indicate any unusual burials compared to other months or summers. Sunset Garden possesses a loose-leaf notebook with the typewritten records of the all the bodies moved there. There are a handful who died in 1917, none of them even close to the time of the pogrom in early July. Same for the burials from St. Clair Cemetery, a public cemetery that closed in 1936. The interment records for the two African American cemeteries that existed at the time across the river in St. Louis are equally silent. Sadly, this is not an exceptional story. The burial space for those killed in the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, or at least some of them, has only recently been excavated at Oaklawn Cemetery.(1)

So, what happened to the rest of the bodies? The best guess is that the State moved the bodies that had grave markers at Douglas and gave them new markers. It’s hard to imagine that the construction crew didn’t overturn any bones when creating the expressway on-ramp; they either didn’t notice or, more likely, chose not to. They had a highway to build, and these were the remains of Black bodies.

So, who buried the dead from the East St. Louis pogrom, and where? Carlos Hurd inferred that Nash and Green had the gruesome tasks of embalming and preparing at least some individuals, but the burial sites themselves remain a mystery, and the actual final resting place even bigger one. This is not a story of Jim Crow burying the dead in 1917, though. It’s about Jim Crow moving their remains. Or not. Or some of each. And no one cared enough to document where they went, not in 1968 and, oddly enough, not in 2024 either.

Notes

Ben Fenwick, “Mass Grave Unearthed in Tulsa During Search for Massacre Victims,” New York Times, October 21, 2020.

About the Author

Dr. Jeffrey Smith is professor emeritus of history now living in St. Louis, Missouri. He is author of The Rural Cemetery Movement: Places of Paradox in Nineteenth-Century America (2017), “‘Every Soldier’s Grave a Shrine’: Confederate Cemetery Monuments,” in Monuments, Memory, and Commemoration: Opportunities, Challenges, and Controversies 92023), and “Till Death Keeps Us Apart: Segregation and Social Values in Cemeteries in St. Louis, Missouri,” in Till Death Do Us Part: Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed (2020). He has written widely on cemeteries and commemoration for publications including the Washington Post, History News, and the History News Network. He is a member of the board of directors of the Fr. Moses Dickson Cemetery, a historic African American cemetery on the National Register of Historic Places. He is currently completing a book manuscript, Grave Mistakes: Uses and Misuses of Cemeteries in America, as well as a social history of Green Lawn Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio.